What is a vulnerability and what is not?

0.041 Low

EPSS

Percentile

92.2%

It looks like a pretty simple question. I used it to started my MIPT lecture. But actually the answer is not so obvious. There are lots of formal definitions of a vulnerability. For example in NIST Glossary there are 17 different definitions. The most popular one (used in 13 documents) is:

> Vulnerability is a weakness in an information system, system security procedures, internal controls, or implementation that could be exploited or triggered by a threat source

NISTIR 7435 The Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) and Its Applicability to Federal Agency Systems

But I prefer this one, it’s from the glossary as well:

> Vulnerability is a bug, flaw, weakness, or exposure of an application, system, device, or service that could lead to a failure of confidentiality, integrity, or availability.

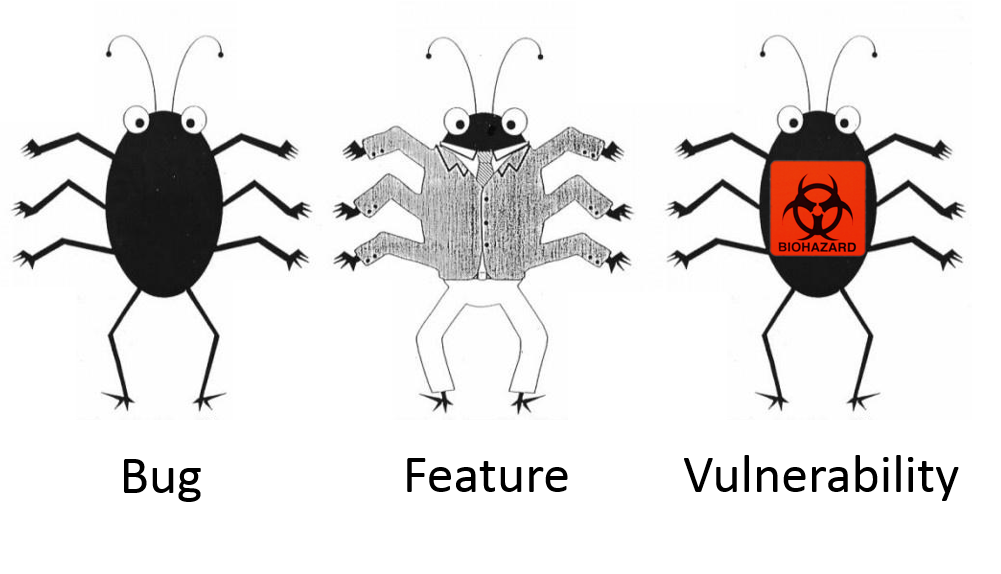

I think the best way to talk about vulnerabilities is to treat them as bugs and errors. Because people deal with such entities more often in a form of software freezes and BSODs.

You probably heard a joke, that a bug can be presented as a feature if it is well-documented and the software developers don’t want to fix it.

Vulnerability is also a specific bug that can lead to some security issues. Or at least it is declared.

Is this particular bug a Vulnerability or not?

Here is also a mind game. How can we say if these particular bug is a vulnerability or not? Well, we can say, that if Confidentiality, Availability or Integrity are affected, it is a vulnerability. For some cases, like my examples of Vulnerable Web-Applications, it’s obvious that those bugs are in fact vulnerabilities. But it’s not always like this.

Should the application data be stored in encrypted form?

For example, in October of last year there was a news that Telegram Messenger stores data on a device in unencrypted SQLite database:

> While it’s somewhat difficult to sift through (write some capable python scripts?) - similar to the issue with Signal - @telegram stores your messages in an unencrypted SQLite database. At least I didn’t have to go through the effort to find the key this time :)) pic.twitter.com/gTRpSKVQAM

>

> – Nathaniel Suchy (@nathanielrsuchy) October 30, 2018

But should each application store it’s data in encrypted form? Telegram CEO, Pavel Durov, released a statement (rus) that it was NOT a vulnerability: “If I had access to Your computer, I would be able to read Your messages”. And he may be right or may be not, depends on your position.

Vulnerability or default misconfiguration?

Another vulnerability that was discovered last October. Unprivileged Linux user could add arbitrary string to X server logs and redirect these logs to /etc/shadows file. Thus, it was possible to change root password.

> #CVE-2018-14665 - a LPE exploit via <https://t.co/eax3fvaAjE> fits in a tweet

cd /etc; Xorg -fp “root::16431:0:99999:7:::” -logfile shadow :1;su

Overwrite shadow (or any) file on most Linux, get root privileges. *BSD and any other Xorg desktop also affected.

>

> – Hacker Fantastic (@hackerfantastic) October 25, 2018

I tried and it actually worked:

> Lol. It works.  Tweetable Exploit by @hackerfantastic for <https://t.co/f6XXfwufVX> Server Local Privilege Escalation (CVE-2018-14665). It fills /etc/shadow with trash, but leaves one correctly interpreted line setting empty password for root. pic.twitter.com/fkEMPCyxkt

Tweetable Exploit by @hackerfantastic for <https://t.co/f6XXfwufVX> Server Local Privilege Escalation (CVE-2018-14665). It fills /etc/shadow with trash, but leaves one correctly interpreted line setting empty password for root. pic.twitter.com/fkEMPCyxkt

>

> – Alexander Leonov (@leonov_av) October 26, 2018

Of course, it was only possible because the X server was installed with the setuid bit set by default. So, was it a vulnerability of X server, default misconfiguration of a Linux distro or maybe even just a feature? It also depends on your point of view. But any way, an attacker still could exploit it.

Vulnerabilities exploitable in very specific conditions

The previous two examples were obviously exploitable, but it’s not the fact that they were, strictly speaking, software vulnerabilities. How about issues that certainly looks like vulnerabilities, but it’s not the fact that they are actually exploitable? It’s very often situation with cryptography issues, with SSL especially.

For example vulnerabilities of 64-bit block ciphers exploitable through sweet32 attack. You might face it during your perimeter PCI ASV scans and will have to deal with it to get a certificate. The problem with this attack is that it needs 32 GB of traffic to decrypt only one session. The researchers say that “is easily reached in practice”, but actually I don’t think so. Most services don’t operate with such amounts of traffic and the session will expire much faster. So, it will be also up to you to decide if this vulnerability is real or not.

In conclusion

> Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

And vulnerability in the eye of the analyst. Software vendors and vulnerability researchers can argue as long as they want about the terms, criticality, who is responsible and who should fix it. But the final decision whether we are dealing with something dangerous or it’s some kind of nonsense makes the security analyst of a particular organization. This analyst also decides what to do next: how to actually fix the vulnerability or what workarounds can be used.